The End Goes On (and On):

Bela Tarr's The Turin Horse *

originally published in MACHETE #19, September 2012

*This essay won the 2012 Canadian Art Foundation Writing Prize (see Press Release)

_

In The Turin Horse, Bela Tarr’s latest and reportedly last film, the Hungarian filmmaker follows Samuel Beckett’s path of impoverishment and subtraction as far as one can imagine in the cinema. This is not a matter of simple minimalism. To construct a form through which to perceive a void, for Tarr as for Beckett, requires bold contortions of aesthetic invention. Having already established himself as the most stubbornly modernist of contemporary auteurs, Tarr has ended his career with possibly his most radical film to date.

A Philosophic Parable

The Turin Horse begins in darkness as a narrator provides a slightly bemused recounting of Nietzsche’s storied final moments of sanity:

In Turin on January 3rd, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway of number six Via Carlo Alberto, perhaps to take a stroll, perhaps to go by the post office to collect his mail. Not far from him, or indeed very far removed from him, the driver of a hansom cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver – Giuseppe? Carlo? Ettore? – loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and that puts an end to the brutal scene caused by the driver, by this time foaming at the mouth with rage. For the solidly built and full-moustached gentleman suddenly jumps up to the cab and throws his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words (“Mutter, ich bin dumm.”), and lives for another ten years, silent and demented, under the care of his mother and sisters. We do not know what happened to the horse.

Following this prologue is the first image of the film, a virtuosic tracking shot lasting several minutes showing a horse pulling on old man on a cart. As Mihaly Vig’s dirge-like score is introduced, we watch the horse labor on from a variety of shifting perspectives. Inevitably, we initially assume that this is the Turin horse and that the film is going to speculate on the lingering question of what became of the animal after the fateful encounter with full-moustached philosopher. However, the Nietzsche incident is never referenced in the film, and besides the period in which the film is set, there is little to connect it directly to the events of prologue. While the horse in the film does refuse to move at one point, this occurs outside the stable where the animal sleeps rather than in a public square. The cold, brutal, wind-ravaged landscape of the film certainly isn’t Turin. The characters speak Hungarian and drink palinka. While the narrator speculates on the Italian name of the Turin cabbie, he refers to horse’s elderly owner in the film as Ohlsdorfer. There seems to be little doubt that we are in Hungary, far from number six Via Carlo Alberto.

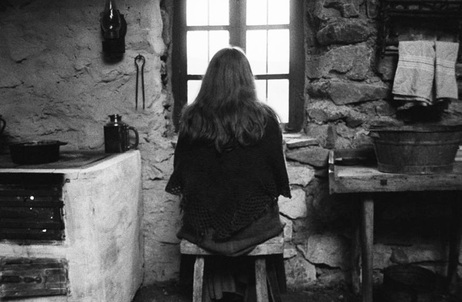

The film’s story, such as it is, focuses on the horse’s owners more than the animal itself. Ohlsdorfer lives in an isolated hut with his middle-aged daughter. He has one lame arm, and she dresses him (the same clothes everyday) and cooks his meals (a shot of palinka for breakfast, a boiled potato for dinner). For entertainment, they take turns sitting in front of their small window gazing catatonically out at the baron landscape. The film takes place over six (presumably) consecutive days. On the first day, Ohlsdorfer and his daughter labor in the howling wind to saddle the horse and fasten their cart to it, only to have the animal stubbornly refuse to move. Ohlsdorfer beats the horse until his daughter convinces him that it’s useless. They unsaddle the animal and go back inside. The next five days chart a quiet apocalypse as the world around them mysteriously grinds to a halt. The horse refuses to eat. Their well dries up. The nearby village is reportedly wiped out. The wind ceases. The oil in their lamps won’t catch fire. Nietzsche may have lived on silent and demented for ten years, but it seems unlikely that anyone in Tarr’s film makes it past day seven.

Rather than searching for a direct connection between the prologue and Tarr’s characters, it is more fruitful to see it as having an indirect and ambivalent relationship to the rest of the film. As a mysterious and apocalyptic tale of empathy and despair precipitating a cataclysmic collapse that snuffs out in an instant and yet lingers on agonizingly, the Nietzsche story functions as a parable mirroring the film’s elusive themes.

The prologue also serves to implicitly suggest Tarr’s view of the relationship of cinema to philosophy. Characters often philosophize aloud in Tarr’s films. This usually takes the form of semi-coherent rants, a superb example of which can be found in The Turin Horse. A neighbor bursts in on Ohlsdorfer and his daughter one day asking to buy a bottle of their palinka. He then sits down and launches unprovoked into a bitter, paranoid metaphysical rant, beautifully written by Tarr’s collaborator, novelist László Krasznahorkai. Speculating on the impossibility of the good and the inseparable forces of acquisition and debasement that rule the world, the neighbor rambles for five full minutes, the only scene of sustained dialogue in the film. When he finally finishes his diatribe, Ohlsdorfer grunts “That’s nonsense,” and the neighbor shrugs and leaves.

Such scenes serve several functions for Tarr. Through them, he acknowledges the impulse to wrestle with philosophical questions; he confirms that his film is partaking in this impulse; he simultaneously demystifies and poeticizes the impulse by having it acted out by drunken, half-mad characters; and, he demonstrates the limits of language and rationality in engaging this impulse (at least in the cinema).

It is characteristic of Tarr’s approach that he highlights the unknown, and unknowable, experience of the horse in the Turin parable. For Tarr, the cinema philosophizes by plunging in the opposite direction from philosophy, into that with which philosophy cannot adequately engage. The end of philosophy for Nietzsche is the starting point for Tarr’s cinema.

In The Turin Horse, Bela Tarr’s latest and reportedly last film, the Hungarian filmmaker follows Samuel Beckett’s path of impoverishment and subtraction as far as one can imagine in the cinema. This is not a matter of simple minimalism. To construct a form through which to perceive a void, for Tarr as for Beckett, requires bold contortions of aesthetic invention. Having already established himself as the most stubbornly modernist of contemporary auteurs, Tarr has ended his career with possibly his most radical film to date.

A Philosophic Parable

The Turin Horse begins in darkness as a narrator provides a slightly bemused recounting of Nietzsche’s storied final moments of sanity:

In Turin on January 3rd, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway of number six Via Carlo Alberto, perhaps to take a stroll, perhaps to go by the post office to collect his mail. Not far from him, or indeed very far removed from him, the driver of a hansom cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver – Giuseppe? Carlo? Ettore? – loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and that puts an end to the brutal scene caused by the driver, by this time foaming at the mouth with rage. For the solidly built and full-moustached gentleman suddenly jumps up to the cab and throws his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words (“Mutter, ich bin dumm.”), and lives for another ten years, silent and demented, under the care of his mother and sisters. We do not know what happened to the horse.

Following this prologue is the first image of the film, a virtuosic tracking shot lasting several minutes showing a horse pulling on old man on a cart. As Mihaly Vig’s dirge-like score is introduced, we watch the horse labor on from a variety of shifting perspectives. Inevitably, we initially assume that this is the Turin horse and that the film is going to speculate on the lingering question of what became of the animal after the fateful encounter with full-moustached philosopher. However, the Nietzsche incident is never referenced in the film, and besides the period in which the film is set, there is little to connect it directly to the events of prologue. While the horse in the film does refuse to move at one point, this occurs outside the stable where the animal sleeps rather than in a public square. The cold, brutal, wind-ravaged landscape of the film certainly isn’t Turin. The characters speak Hungarian and drink palinka. While the narrator speculates on the Italian name of the Turin cabbie, he refers to horse’s elderly owner in the film as Ohlsdorfer. There seems to be little doubt that we are in Hungary, far from number six Via Carlo Alberto.

The film’s story, such as it is, focuses on the horse’s owners more than the animal itself. Ohlsdorfer lives in an isolated hut with his middle-aged daughter. He has one lame arm, and she dresses him (the same clothes everyday) and cooks his meals (a shot of palinka for breakfast, a boiled potato for dinner). For entertainment, they take turns sitting in front of their small window gazing catatonically out at the baron landscape. The film takes place over six (presumably) consecutive days. On the first day, Ohlsdorfer and his daughter labor in the howling wind to saddle the horse and fasten their cart to it, only to have the animal stubbornly refuse to move. Ohlsdorfer beats the horse until his daughter convinces him that it’s useless. They unsaddle the animal and go back inside. The next five days chart a quiet apocalypse as the world around them mysteriously grinds to a halt. The horse refuses to eat. Their well dries up. The nearby village is reportedly wiped out. The wind ceases. The oil in their lamps won’t catch fire. Nietzsche may have lived on silent and demented for ten years, but it seems unlikely that anyone in Tarr’s film makes it past day seven.

Rather than searching for a direct connection between the prologue and Tarr’s characters, it is more fruitful to see it as having an indirect and ambivalent relationship to the rest of the film. As a mysterious and apocalyptic tale of empathy and despair precipitating a cataclysmic collapse that snuffs out in an instant and yet lingers on agonizingly, the Nietzsche story functions as a parable mirroring the film’s elusive themes.

The prologue also serves to implicitly suggest Tarr’s view of the relationship of cinema to philosophy. Characters often philosophize aloud in Tarr’s films. This usually takes the form of semi-coherent rants, a superb example of which can be found in The Turin Horse. A neighbor bursts in on Ohlsdorfer and his daughter one day asking to buy a bottle of their palinka. He then sits down and launches unprovoked into a bitter, paranoid metaphysical rant, beautifully written by Tarr’s collaborator, novelist László Krasznahorkai. Speculating on the impossibility of the good and the inseparable forces of acquisition and debasement that rule the world, the neighbor rambles for five full minutes, the only scene of sustained dialogue in the film. When he finally finishes his diatribe, Ohlsdorfer grunts “That’s nonsense,” and the neighbor shrugs and leaves.

Such scenes serve several functions for Tarr. Through them, he acknowledges the impulse to wrestle with philosophical questions; he confirms that his film is partaking in this impulse; he simultaneously demystifies and poeticizes the impulse by having it acted out by drunken, half-mad characters; and, he demonstrates the limits of language and rationality in engaging this impulse (at least in the cinema).

It is characteristic of Tarr’s approach that he highlights the unknown, and unknowable, experience of the horse in the Turin parable. For Tarr, the cinema philosophizes by plunging in the opposite direction from philosophy, into that with which philosophy cannot adequately engage. The end of philosophy for Nietzsche is the starting point for Tarr’s cinema.

Stubbornly Uncertain

Ailing bodies, political instability, the volatility of human relationships, the unknowability of animals, the limits of communication, the deceptive nature of logic, the precariousness of sanity, the insatiability of needs and desires, the unreliability of pleasure, the confinements of family/community/location, the haphazard tyranny of the weather: these are the defining features of Tarr’s cinematic universe. In this sense, The Turin Horse functions well as a summation of his body of work. The metaphysical, existential, ontological precariousness that haunts Tarr’s other films becomes the sole subject of The Turin Horse, which could be described as an aesthetically precise and exacting parable of vagueness and indeterminacy.

For Tarr, given this fundamental precariousness, nothing is more dangerous and contagious than despair. A spark of despair can turn the world to ash in Tarr’s universe, and much of his late work charts the slow, creeping, apocalyptic arc from uncertainty to apathy to despair. Walking, of course, features prominently in Tarr’s films. Walking and weather. Long chunks of screen time are given over to characters laboriously battling brutal wind, one step at a time. For Tarr, this functions both as a realistic depiction of life, and as a simple, visceral metaphor for it. Without faith or purpose, one must trudge on. There is no redemption to be found in Tarr’s vision, not even the kind Camus finds in the Sisyphus myth. Sisyphus could be happy because he knew his fate and so he could accept it. We, on the other hand, don’t know what’s in store for us from one step to the next, never mind beyond that, though all indications suggest things will get worse and worse . The tedium is always fraught with the likelihood of catastrophe. But we must go on regardless, for as long as we can, because, of course, it is not up to us in the end.

Tarr’s vision aligns well with Beckett’s famous last words in The Unnamable ( “in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I will go on.”). However, Tarr counters the misleadingly triumphant tenor the phrase can take on when presented, as it often is, as a kind of epigram for Beckett’s worldview: to go on is no feat to be applauded, it is not even necessarily desirable, it is simply the burdensome fundamental condition of existence. Both Tarr and Beckett are artists of purgatory, and their differences have less to do with perspective than medium. Writing, for Beckett, mirrors interiority, speaks of wrestling with the seemingly useless, unrelenting, confounding experience of consciousness. The cinema, for Tarr, stages exteriority, observes the mysterious, interdependent relationships between unknowable beings (human or animal) and the seemingly indifferent world that they inhabit and that dictates the confines of their existence.

Tarr refuses to stage a satisfying apocalyptic finale. In Tarr’s films, even the apocalypse is robbed of its grandiosity and finality, is rendered provisional and uncertain. Every moment is apocalyptic, headed inevitably toward the end, and yet no end arrives. The seventh day is never shown in the film. On the one hand, there is no need to show it. Rationally, we know what will happen. The village is gone. Everyone has vanished. They have no water. Fire won’t burn. At the end of the sixth day, Ohlsdorfer and his daughter sit at their table in darkness, each trying to force down a raw potato. And yet, we see them. In the last shot of his career, Tarr gives us light where there is none. This can hardly be viewed as an uplifting gesture of hope, as it allow us only to witness inevitable suffering longer than we would otherwise be able to. Nonetheless, there is something modestly, even bleakly, affirmative in this simple final gesture, which attests to Tarr’s refusal to deflect uncomfortable truths with a spectacle of finality he doesn’t believe in.

Ailing bodies, political instability, the volatility of human relationships, the unknowability of animals, the limits of communication, the deceptive nature of logic, the precariousness of sanity, the insatiability of needs and desires, the unreliability of pleasure, the confinements of family/community/location, the haphazard tyranny of the weather: these are the defining features of Tarr’s cinematic universe. In this sense, The Turin Horse functions well as a summation of his body of work. The metaphysical, existential, ontological precariousness that haunts Tarr’s other films becomes the sole subject of The Turin Horse, which could be described as an aesthetically precise and exacting parable of vagueness and indeterminacy.

For Tarr, given this fundamental precariousness, nothing is more dangerous and contagious than despair. A spark of despair can turn the world to ash in Tarr’s universe, and much of his late work charts the slow, creeping, apocalyptic arc from uncertainty to apathy to despair. Walking, of course, features prominently in Tarr’s films. Walking and weather. Long chunks of screen time are given over to characters laboriously battling brutal wind, one step at a time. For Tarr, this functions both as a realistic depiction of life, and as a simple, visceral metaphor for it. Without faith or purpose, one must trudge on. There is no redemption to be found in Tarr’s vision, not even the kind Camus finds in the Sisyphus myth. Sisyphus could be happy because he knew his fate and so he could accept it. We, on the other hand, don’t know what’s in store for us from one step to the next, never mind beyond that, though all indications suggest things will get worse and worse . The tedium is always fraught with the likelihood of catastrophe. But we must go on regardless, for as long as we can, because, of course, it is not up to us in the end.

Tarr’s vision aligns well with Beckett’s famous last words in The Unnamable ( “in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I will go on.”). However, Tarr counters the misleadingly triumphant tenor the phrase can take on when presented, as it often is, as a kind of epigram for Beckett’s worldview: to go on is no feat to be applauded, it is not even necessarily desirable, it is simply the burdensome fundamental condition of existence. Both Tarr and Beckett are artists of purgatory, and their differences have less to do with perspective than medium. Writing, for Beckett, mirrors interiority, speaks of wrestling with the seemingly useless, unrelenting, confounding experience of consciousness. The cinema, for Tarr, stages exteriority, observes the mysterious, interdependent relationships between unknowable beings (human or animal) and the seemingly indifferent world that they inhabit and that dictates the confines of their existence.

Tarr refuses to stage a satisfying apocalyptic finale. In Tarr’s films, even the apocalypse is robbed of its grandiosity and finality, is rendered provisional and uncertain. Every moment is apocalyptic, headed inevitably toward the end, and yet no end arrives. The seventh day is never shown in the film. On the one hand, there is no need to show it. Rationally, we know what will happen. The village is gone. Everyone has vanished. They have no water. Fire won’t burn. At the end of the sixth day, Ohlsdorfer and his daughter sit at their table in darkness, each trying to force down a raw potato. And yet, we see them. In the last shot of his career, Tarr gives us light where there is none. This can hardly be viewed as an uplifting gesture of hope, as it allow us only to witness inevitable suffering longer than we would otherwise be able to. Nonetheless, there is something modestly, even bleakly, affirmative in this simple final gesture, which attests to Tarr’s refusal to deflect uncomfortable truths with a spectacle of finality he doesn’t believe in.