Michael Haneke and

The White Ribbon

originally published in MACHETE #5, February 2010

-‘When did the gaze collapse?’

-‘Before TV took precedence.’

-‘Took precedence over what? Current events?’

-‘Over life.’

-‘Yes. I feel our gaze has become a program under control, subsidized. The image, the only thing capable of denying nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness on us.’

- Jean-Luc Godard’s Eloge de L’Amour

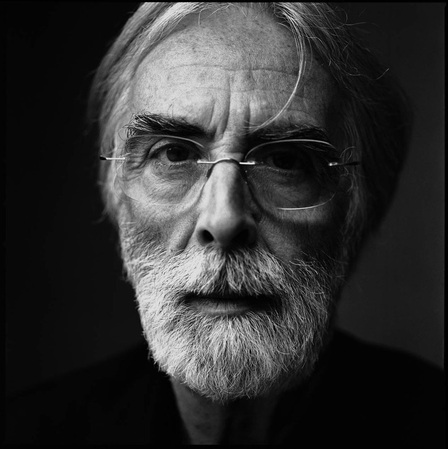

In many ways, Michael Haneke stands virtually alone in contemporary cinema. One of the most the most divisive and controversial filmmakers working today, what has set Haneke apart from other cinematic provocateurs is the consistency with which his provocations have remained committed to a rigorous and unflinching critique of contemporary Western culture. Philosophically rooted in the modern German tradition of Nietzsche-Freud-Marx and its development in the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, in particular Adorno, Haneke’s critical vision is as ambitious in scope as it is attentive to the (often toxic) minutia of the present. Crucial to this critique, as well as to Haneke’s bold, austere aesthetic, is his ruthless acknowledgment of the degree to which contemporary life is inseparable from the influence of the cinema, television and the culture of media images in general. There is perhaps no major filmmaker today, aside from Godard, who has fused such a sophisticated and original cinematic practice with such a brazenly polemical insistence on implicating the culture of images in a sustained critique of contemporary culture as a whole.

There is a contradiction at the heart of Haneke’s cinema that is not often remarked upon. Cinematically his pedigree is almost exclusively the modernist tradition of mid-century European auteurs: Antonioni, Godard, Passolini, Bunuel, and his most eagerly acknowledged influence, Bresson. However, stylistically Haneke is a staunch realist. There is nothing in Haneke’s cinema like Bresson’s idiosyncratically austere use of non-professional ‘models’, and certainly nothing of the unique idiom of essayistic montage Godard has developed. With every element of his films – the acting, the dialogue, the photography, the settings, the sound and music – Haneke favors a strictly naturalistic approach. His stylizations reveal themselves mostly in his predilection for fragmentation (of narrative and mise-en-scene), as well his deft experiments with duration (shots held well past the point of comfort). His basic approach is to reproduce the texture and details of contemporary life, but then to present it cinematically in such a way that it becomes unsettlingly unfamiliar as the violence and structural oppression beneath the surface of everyday reality reveals itself. This approach is frequently punctuated by a sudden shock-moment in which we are ripped out of the onscreen narrative and confronted with the fact that we are experiencing a cinematic image, a constructed reality. These moments include the horrific scenes in Code Unknown that are later revealed to be dubbing sessions for a film, the unease created by the mysterious videotapes in Cache, and of course the infamous fourth-wall shattering ‘rewind’ scene in Funny Games. The effectiveness of these shock-moments is wholly dependant on Haneke’s mastery as a realist – it is the sudden betrayal of the impeccably achieved naturalism that produces their unsettling power. Such moments make explicit what is implied throughout the rest of the films: for Haneke, realism always presents a double bind, it is always ‘realism’, a construction of reality that he challenges us to acknowledge as such, even as he continues seducing us with his skill as a realist, tempting us to accept the seemingly flawless reality uncritically and then punishing us when we succumb to these temptations. In this way, the usually conservative impulse toward conventional naturalism ends up producing radical social critique in Haneke’s hands.

-‘Before TV took precedence.’

-‘Took precedence over what? Current events?’

-‘Over life.’

-‘Yes. I feel our gaze has become a program under control, subsidized. The image, the only thing capable of denying nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness on us.’

- Jean-Luc Godard’s Eloge de L’Amour

In many ways, Michael Haneke stands virtually alone in contemporary cinema. One of the most the most divisive and controversial filmmakers working today, what has set Haneke apart from other cinematic provocateurs is the consistency with which his provocations have remained committed to a rigorous and unflinching critique of contemporary Western culture. Philosophically rooted in the modern German tradition of Nietzsche-Freud-Marx and its development in the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, in particular Adorno, Haneke’s critical vision is as ambitious in scope as it is attentive to the (often toxic) minutia of the present. Crucial to this critique, as well as to Haneke’s bold, austere aesthetic, is his ruthless acknowledgment of the degree to which contemporary life is inseparable from the influence of the cinema, television and the culture of media images in general. There is perhaps no major filmmaker today, aside from Godard, who has fused such a sophisticated and original cinematic practice with such a brazenly polemical insistence on implicating the culture of images in a sustained critique of contemporary culture as a whole.

There is a contradiction at the heart of Haneke’s cinema that is not often remarked upon. Cinematically his pedigree is almost exclusively the modernist tradition of mid-century European auteurs: Antonioni, Godard, Passolini, Bunuel, and his most eagerly acknowledged influence, Bresson. However, stylistically Haneke is a staunch realist. There is nothing in Haneke’s cinema like Bresson’s idiosyncratically austere use of non-professional ‘models’, and certainly nothing of the unique idiom of essayistic montage Godard has developed. With every element of his films – the acting, the dialogue, the photography, the settings, the sound and music – Haneke favors a strictly naturalistic approach. His stylizations reveal themselves mostly in his predilection for fragmentation (of narrative and mise-en-scene), as well his deft experiments with duration (shots held well past the point of comfort). His basic approach is to reproduce the texture and details of contemporary life, but then to present it cinematically in such a way that it becomes unsettlingly unfamiliar as the violence and structural oppression beneath the surface of everyday reality reveals itself. This approach is frequently punctuated by a sudden shock-moment in which we are ripped out of the onscreen narrative and confronted with the fact that we are experiencing a cinematic image, a constructed reality. These moments include the horrific scenes in Code Unknown that are later revealed to be dubbing sessions for a film, the unease created by the mysterious videotapes in Cache, and of course the infamous fourth-wall shattering ‘rewind’ scene in Funny Games. The effectiveness of these shock-moments is wholly dependant on Haneke’s mastery as a realist – it is the sudden betrayal of the impeccably achieved naturalism that produces their unsettling power. Such moments make explicit what is implied throughout the rest of the films: for Haneke, realism always presents a double bind, it is always ‘realism’, a construction of reality that he challenges us to acknowledge as such, even as he continues seducing us with his skill as a realist, tempting us to accept the seemingly flawless reality uncritically and then punishing us when we succumb to these temptations. In this way, the usually conservative impulse toward conventional naturalism ends up producing radical social critique in Haneke’s hands.

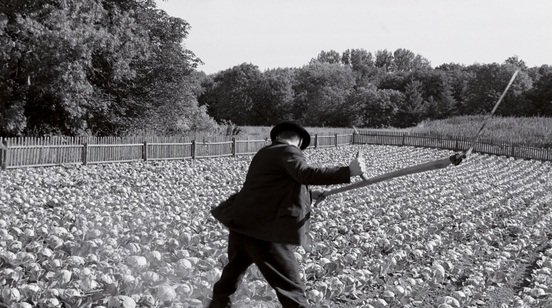

Haneke's acclaimed new film, The White Ribbon, won the Palm D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival last year and was nominated for a Best Foreign Film Oscar. Indeed, it is an easy film to admire, featuring superb performances, stunning black and white photography, a subtle and original script, unsettling themes, etc. In many ways, it is very much in keeping with his previous work. It examines systemic violence, repression, and social oppression, and illustrates the ways these are passed on from one generation to the next – it could be viewed as a kind of thematic counterpart to Cache. The difference is that unlike all of Haneke’s other features, The White Ribbon is not set in the contemporary world. The film takes place in a village in the Austro-Hungarian Empire that is unsettled by a series of mysterious violent incidents in the years preceding the outbreak of World War One. It is a chilling portrait of a community locked in a deteriorating cycle of Nietzschean resentiment, a psychologically and philosophically lacerating illustration of the ways in which injustice, inequality and exploitation breeds hatred and repression, and of the ways in which moral authoritarianism and ideological fanaticism leave room only for cruelty and violence, whether in rebellion or in acquiescence. It is surely meant as a kind of parable not only for the German descent into fascism that occurs in the years immediately following those portrayed in the film, but also for our own contemporary age of terrorism. As such it is certainly of interest, and one can imagine why Haneke might be tempted to explore his usual themes in a different historical setting, thereby broadening the critique of Western culture. And yet, removing this critique from the present comes at a cost. The effectiveness of Haneke’s naturalistic approach is considerably dampened when it is removed from a contemporary context. The tension he has become such a master at generating, which is rooted in the ontological uncertainty between image and reality as it is experienced both onscreen and in contemporary life, and which is the explosive core of his aesthetic, is necessarily absent from The White Ribbon, set as it is in a period preceding the age of the image.

Haneke’s previous film before The White Ribbon was Funny Games, his critically reviled and commercially unsuccessful American shot-for-shot remake of his controversial 1997 German film of the same name. Haneke’s quasi-sadistic method of critique reaches its apotheosis in Funny Games, which takes the self-betraying and untenable ‘game’ of cinematic realism as it’s structuring principal and mounts an almost unbearable polemic on the relationship between violence and the image in a culture saturated by both. It is not surprising that such a an openly confrontational film failed to engage American audiences and critics, and so it is understandable, if perhaps disappointing, that after this attempt at mainstream subversion proved commercially unsuccessful (and failed to receive the serious of critical appraisal it deserved), Haneke has decided to retreat to the safer shores of an art-house period piece, which, for all its unsettling power and meticulous realization, ultimately lets viewers contemplate a fable about the roots of evil from a comfortable distance.

The White Ribbon may well be a masterpiece – but is it the kind of masterpiece we need? I, for one, will hold out hope that after basking in the justly deserved establishment praise, Haneke will return to his more crucial role as a divisive polemicist and critic of the present.

Haneke’s previous film before The White Ribbon was Funny Games, his critically reviled and commercially unsuccessful American shot-for-shot remake of his controversial 1997 German film of the same name. Haneke’s quasi-sadistic method of critique reaches its apotheosis in Funny Games, which takes the self-betraying and untenable ‘game’ of cinematic realism as it’s structuring principal and mounts an almost unbearable polemic on the relationship between violence and the image in a culture saturated by both. It is not surprising that such a an openly confrontational film failed to engage American audiences and critics, and so it is understandable, if perhaps disappointing, that after this attempt at mainstream subversion proved commercially unsuccessful (and failed to receive the serious of critical appraisal it deserved), Haneke has decided to retreat to the safer shores of an art-house period piece, which, for all its unsettling power and meticulous realization, ultimately lets viewers contemplate a fable about the roots of evil from a comfortable distance.

The White Ribbon may well be a masterpiece – but is it the kind of masterpiece we need? I, for one, will hold out hope that after basking in the justly deserved establishment praise, Haneke will return to his more crucial role as a divisive polemicist and critic of the present.